|

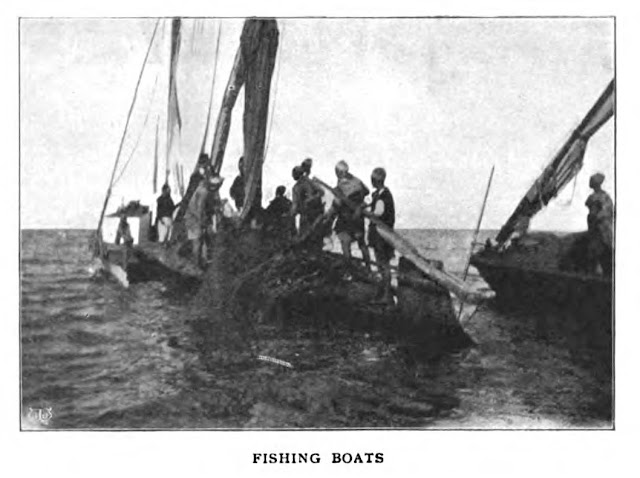

| قوارب صيد |

|

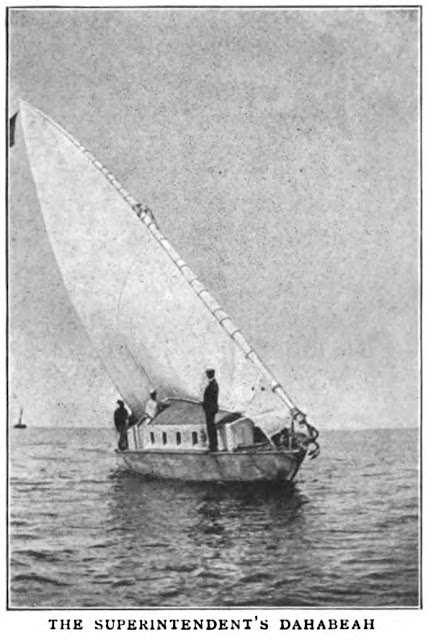

| دهبية ناظر مصلحة الأسماك |

|

| صياد في البحيرة |

|

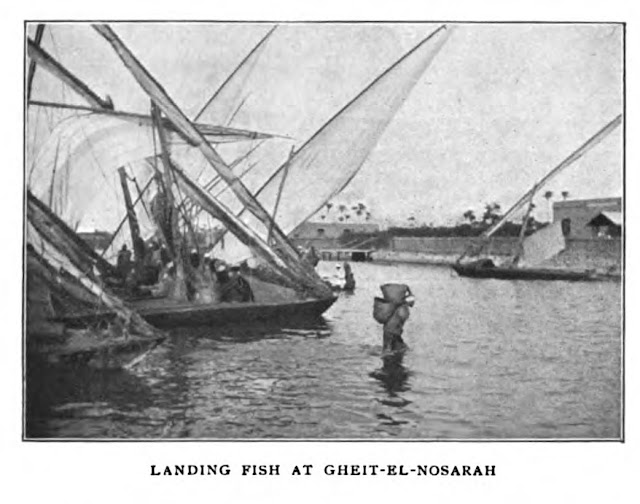

| تفريغ الأسماك في غيط النصارى |

|

| رتق شباك الصيد |

|

| في الطريق لدمياط من غيط النصارى |

|

| في الطريق لدمياط من غيط النصارى |

|

| ناصية شارع في دمياط |

|

| بياع ليمونادة في دمياط |

Source: THE BADMINTON MAGAZINE, Volume XVII. July to December 1903 (Link)

ON LAKE MENZALEH

BY CHARLES E. ELDRED, R.N.

Whoever has passed through the Suez Canal must have noticed

that near the Port Said end the western bank is for a long distance

no more than an embankment between the Canal and a sheet of

water stretching to the horizon. The muddy margin fringed

with a scanty growth of reeds, and the numerous islets almost level with

the water, suggest with some truth that this Lake is no more than a

vast shallow swamp.

The crossing of this swamp is a prospect which does not promise

to supply either excitement or interest. Yet, having safely done

so, one will thereafter count Lake Menzaleh amongst those things

which are not what they seem. For, incredible as it may appear,

this is one of the most valuable tracts of the Khedive's dominions.

The extensive fishing industry carried on upon the Lake brings into

the Egyptian territory a sum of about £50,000 annually from the

licences and other dues paid by the fishermen.

Of the varied duties of the Egyptian Coastguard force, one is

the supervision and control of these Lake fisheries. The Coast-

guard, like many other Egyptian services, is under the management

of Englishmen ; and the privilege of accompanying the Superintend-

ing Officer on an inspection tour on the Lake is one to be by no

means lightly valued. In every incident there is something sur-

prising or unexpected. The traveller starts by being carried pick-

a-back upon the shoulders of an Egyptian Coastguard across the

muddy foreshore to a small punt, which, although flat bottomed,

cannot be brought within some yards of dry ground. The dry ground

is merely a low, sandy peninsula, on which stand a few Arab fishermen's huts.

Beyond the dark hulls of some most strangely-shaped fishing boats a white

dahabeah gleams in the moonlight. The flat punt is pushed right alongside her,

and no surprise could be greater than to find a vessel of such size floating in water

in which a man can wade up to the thighs. Wonder increases as the sailors set the

single wing-shaped lateen sail. The long tapering yard soaring away slantwise

towards the stars is supported at its centre upon a stout mast, which instead of

being round, as masts usually are, is square. Upon its foremost face a series

of wooden brackets serve for the sailors to go aloft by, to furl or unloose sail.

The mast and spars look as if they would overbalance a 10-ton yacht with a lead

keel. But here is a shallow skimming-dish, with a flimsy-looking superstructure

of curtained windows, drawing twenty inches of water and carrying no ballast,

contradicting all the laws of equilibrium by standing up stubbornly to a fresh

breeze. Another contradiction is to be noticed in the method of shifting the tack

of the sail to one side or the other of the bow with the changes in direction of the wind. The

sheet meanwhile remains secured amidships.

The rig and construction of the Superintendent's dahabeah

resemble in the essentials the smaller and rougher fishing boats.

The difference is to be found in the spacious cabins, the curtained

windows, chintz upholstery, and the culinary refinements in keeping

with these surroundings produced by Mabruk, the black, snowy-clad

Berberine cook-- a craft that might be coveted for a cruise upon

the Norfolk Broads. But in these surroundings one may learn that

the travelling of a Coastguard officer in Egypt is not all performed

in such comfortable circumstances. There are more wearisome

camel journeys across stretches of burning desert as a counter-

balance to this.

The passage across the Lake may occupy anything between six

and eighteen hours, according to the direction and force of the wind.

I am convinced, however, it could never be a tedious one to any

passenger fortunate enough to sail with the host I did. Sitting on

the cabin-roof under the stars, I listened to accounts of journeys

towards all the boundaries of Egypt — of the Upper Nile and the

Western Oasis — of a recent visit to King Solomon's turquoise mines

in the Sinai Peninsula, all told by one with a full appreciation of the

picturesque aspect of things.

An interruption occurs at intervals when the dahabeah takes

the ground very gently. Sometimes she slides over the shoal, some-

times the crew have to push across with poles. Occasionally this

method fails, and then all hands jump into the water and pull the

boat over. In the meantime the Berberine cook has transformed

the chintz couches into sleeping berths.

Daylight brings us amongst clusters of the fishing boats at

work. They are craft as extraordinary in shape as anything that

floats. Their proportion of length to breadth is about that of a

turbot or sole. The curve of the deck from forward to aft is the

reverse of that usual in vessels, being of a hog-backed form. The

space forward of the mast is generally occupied by a mud fire-place,

covered by a sort of turtle-back roof. The long wing-shaped

lateen sails soaring away aloft seem so many protests against the

shallow draught of the hull.

The fishing is performed entirely by nets, but there are several

different fashions of using them, varying slightly. Sometimes the

net forms a semi-circular enclosure stretched on stakes driven into

the mud. By another method the net is pulled through the water

by men wading, and the ends gradually brought together. But any

one of these systems involves a vast splashing and shouting, with a

beating of the boards of the boats to drive the fish into the nets.

Our dahabeah thrusts herself in amongst a cluster of the fishing

boats, so closely packed that Mabruk can step from one to another

and fill a bucket with just such fish as please his eye. They appear

to resemble mullet as closely as anything, and even Mabruk's culi-

nary skill cannot altogether disguise a slightly muddy flavour.

There are fish being landed when we arrive at Gheit-el-Nosarah.

The scene is wanting in the rugged picturesqueness that one asso-

ciates with the fisherman's calling in more Northern climates. The

model market-place, with its cemented floors and washing tanks, the

surrounding salting-houses, with their complete arrangements, are all

most excellent illustrations of the saying that the British can manage

other countries better than their own. Such a background, how-

ever, serves to emphasise the picturesqueness of the Arab crowd,

the bearded sheiks in their flowing robes, the veiled women mending

and making nets, the fishermen wading ashore with their baskets of

fish. Some years ago the management of the Lake fisheries was in

the hands of an Armenian, who kept a stately establishment in the

great yellow-washed building that still retains the name of the

Palace.

The block of modern structures includes the barracks for the

company of Coastguards who form the Lake patrol. Amongst

the many and varied duties of my host there is a kit inspection here.

There are dahabeahs refitting and new ones in course of construc-

tion. There are salting-houses building, and pumps under repair.

There are petitioners waiting with Arabic documents stamped with

mystic seals, fishermen bringing complaints against one another

of infringements of the Fishery Regulations. All this business

has to be conducted in Arabic, and but for the writer's presence

the Superintendent would have spoken nothing else for four days.

Leaving him listening to interminable romances, I set out to

visit the city of Damietta, under the guidance of one of the men of

the Coastguard. As we rode on donkeys he formed a mounted

escort. It was a progress fit for a Pacha. I should not like to say

whether the respect we met with was due to his uniform or because

he made it known that I was a guest of the Bimbashi. But he

shouted to people many yards ahead to stand on one side and get

out of the way. It did not matter whether they were Egyptian

ladies in silks or ragged water-carriers. Indeed, I think the women

met with the least respect. If I stopped to make a sketch at a

street corner, he began to make a general clearance of all the

costermongers' barrows and stalls, and expressed great astonishment

that I interceded for them to remain. But upon looking round after

commencing my sketch I found he had stopped all the traffic, and

that a procession of carts, donkeys, and porters was waiting quite

patiently to proceed.

I attempted to make him understand that I was going to try

to take a photograph of a woman carrying a water-jar on her

head, upon which he immediately laid violent hands on her and put

her in a position of attention facing straight towards me. In truth,

his well-meaning intentions hardly appeared to be any help. But I

realised his consequence when I went alone the next day, and created

difficulties that the police were absolutely powerless to contend with.

If the Pied Piper had been in the town I am convinced his following

would have deserted him to join the retinue at my heels. For I

drew off the greater part of a funeral procession — all but the hired

mourners — and ran a public lunatic, carrying a big stone on his head,

very close in point of popularity.

The word was passed from mouth to mouth, Mesawarati — the

picture-maker. But picture-making soon becomes quite impossible,

and it is only with great difficulty that an occasional sudden snap-

shot with a camera can be got ; and so I trailed a long procession

through the winding thoroughfares of Damietta, amongst buildings

in all stages of decay, the screens of mushebiva work falling to pieces.

In Egypt nothing is ever repaired. One cannot help speculating upon the future of the

few steam rice-mills which have been introduced here, their chimneys forming a violent

contrast to the pointed minarets of the mosques.

In the evenings we lay in wait amongst the fringe of reeds for the wild duck flight-

ing in from the Lake, till the new moon went down and it grew too dark to see along a

gun-barrel. The first shot brings an Egyptian field-labourer on to the scene to earn

a backsheesh by retrieving any birds that fall into the swamps. The chirping of

cicadas and the croaking of frogs grow louder and more incessant with the

falling darkness. The cloudless sunsets have their own beauty in the unbroken

gradation of colour, from the deep blue over head, through shades of delicate

green, to the orange and crimson behind the tall palm trees.

The keenest sportsman might be forgiven for letting the duck rush by unnoticed

if a flight of flamingo should choose to go through their evolutions at this time ; while

the fields and palms below are in shadow, their rose-coloured wings still catch the last

rays of sunlight ; with their legs and neck extended in a perfectly straight line they

resemble winged walking-sticks with knobbed heads. But to what can one compare the

figures of their drill ? At one moment an absolutely unarranged

group ; the next it is split up into companies, which divide and

sub-divide, form and re-form in arrangements which never seem

to repeat themselves. From the cloud there shoots ahead

a line like the flight of a rocket, or there suddenly unfolds in the rear a

string which undulates like a pennon or the tail of a kite or the

motion of a snake. Anon it is a floating string of beads, now loose,

now entangled. Presently the string breaks, and the beads at the

point of being scattered abroad are arrested by an invisible and

magical force. They become a puff of smoke instead, and like a

wreath of smoke they drift away till they merge into the ever-

deepening blue.

When we recross the Lake in the early morning we may pass

some low, flat islands, which appear at a distance to be fringed with

snow. This effect is produced by the flocks of flamingo, whose

legs ought to be considered the unit in gauging the depth of Lake

Menzaleh.

The conspicuous flamingo are not, however, by any means

the only winged inhabitants of the Lake. Marsh birds of every

kind abound in great numbers. Pelican, duck, teal, plover, and

sandpipers all live protected from the gun, shooting being pro-

hibited upon the Lake, though not on the surrounding shores, as it

is supposed to alarm the fish. Duck, however, are caught by snares

and with decoys, and upon the edge of any of the islets may be

seen a little screen of reeds or brushwood, behind which crouches,

motionless and patient, the solitary figure of an Egyptian fowler.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق